What is Environmental Justice?

Let’s start by looking at how the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) defines environmental justice (often abbreviated as EJ):

Environmental justice is the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.

It’s not a perfect definition, and sadly, environmental injustice is often easier for us to wrap our heads around. With our powerful global economy constantly putting profits above people and planet, we see environmental injustice all around us: industrial plants located near public schools, lead paint in low-income housing, and unsafe drinking water in Black neighborhoods.

Defining what environmental justice looks like is a more involved process and requires us to think beyond our current realities and norms. It means allowing ourselves to really imagine the world we want to live in, and examining why we haven’t been able to achieve it thus far. Each example of environmental injustice listed above has a diverse set of stakeholders, all advocating for different solutions. Environmental justice attempts to deliver the most equitable and fair plan for everyone.

The EJ movement has gained more recognition in recent years, and many traditional environmental conservation organizations have begun to incorporate its principles into their messaging, and, to a lesser extent, their work. EJ has its roots in grassroots efforts, with a deep history in civil rights and labor movements — distinct from traditional environmentalism.

How did EJ start?

The first EJ actions were closely tied to the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Labor unions across the US started to demand better working conditions, one notable example being the 1968 Sanitation Workers Strike in Memphis, TN, supported by Dr. Martin Luther King. Early environmental justice activism went hand in hand with civil rights activism.

Other events like Bean v Southwestern Waste Management Corp in 1978, in Houston, Texas, marked the first time the location of a waste facility was contested under civil rights law. However, in this case, the court decided the defendants did not have sufficient evidence to establish intent to discriminate, and the plant was built anyway.

Warren County, 1982

What finally brought the national spotlight onto the issue of environmental justice were the Warren County protests in 1982. A landfill was being proposed in Warren County, North Carolina, and that landfill would contain PCBs, a toxic compound that has been linked to various types of cancer and birth defects.

Local residents organized protests against the landfill, concerned it would cause harm to their community. Warren County was known as one of the poorest counties in the nation, with African Americans making up 65% of the population, and 25% of residents living in poverty. The government refused to reconsider the landfill proposal, despite the location being objectively unsuitable since the water table was about five feet below the surface — all but ensuring the risk of water contamination.

The protests were widely reported and televised, with notable activists and organizations in attendance, such as Benjamin Chavis and the NAACP. The protests spanned six weeks, and more than 500 people were arrested.

Unfortunately, the landfill plans moved forward, but that did not stop the EJ movement. In 1983, Dr. Robert Bullard published one of the first studies showing the relationship between hazardous waste sites and Black neighborhoods in Houston, Texas. The study found that these waste sites were more likely to be located in predominantly Black neighborhoods, despite Black residents only being 25%of the city’s population.

Further studies supported this finding. A study conducted by the US General Accounting Office revealed three out of four hazardous waste landfills in the South were located in Black communities, while Black residents were only 20% of the region’s population. It was blatant environmental racism.

A more comprehensive report, Toxic Waste in the United States, was conducted by the United Church of Christ Commission on Racial Justice in 1987. It confirmed that the determining factor in siting hazardous sites was race, regardless of income. A follow-up report in 2007 showed that the same disparities persisted, even 20 years later.

It’s a problem that’s well-known but not questioned in our country: environmental hazards disproportionately impact BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, & People of Color) communities.

Why does this happen?

While each case of environmental injustice is unique, with a variety of stakeholders, there are a few common threads that can account for why certain communities are targeted for hazardous sites. One important factor is political power, and another is discriminatory housing practices.

Our cities and towns have been built based on zoning laws and land use laws. Most cities in the United States have used a variety of techniques to enforce segregation in housing. The most notable technique, “redlining”, was when the Federal Housing Administration refused to insure mortgages in and around Black neighborhoods.

The term came about because maps were color-coded, and these colors were designed to indicate where it was “safe” to insure mortgages. Red was used to signal to appraisers that the neighborhoods were too “risky”, and basically, anywhere that African-Americans lived was red. Today, similar real estate practices are used to control where people are eligible to buy homes, continuing a long history of discrimination.

As a result, communities of color are frequently located in undesirable areas, typically near industrial zoning. When a new industrial site is proposed, there are several ways environmental injustice can occur.

Zoning commissions often fail to adequately involve the local community in their decision-making. It’d be bad enough that most commissions do not include a person of color, or people who represent the perspectives of the community. But even when there are opportunities for community input, the forums are frequently inaccessible to most residents impacted by the zoning decision.

These forums are often not advertised or widely shared with the community in advance, and are typically scheduled during working hours when most people cannot leave their jobs. To make matters worse, the forums can be located in difficult-to-access areas, far from public transportation, and frequently offered only in English.

More affluent or white communities often have the political, economic, and time resources needed to successfully block hazardous sites from being built near their neighborhoods. And if there are sites near these neighborhoods, pollution regulations are more strictly enforced.

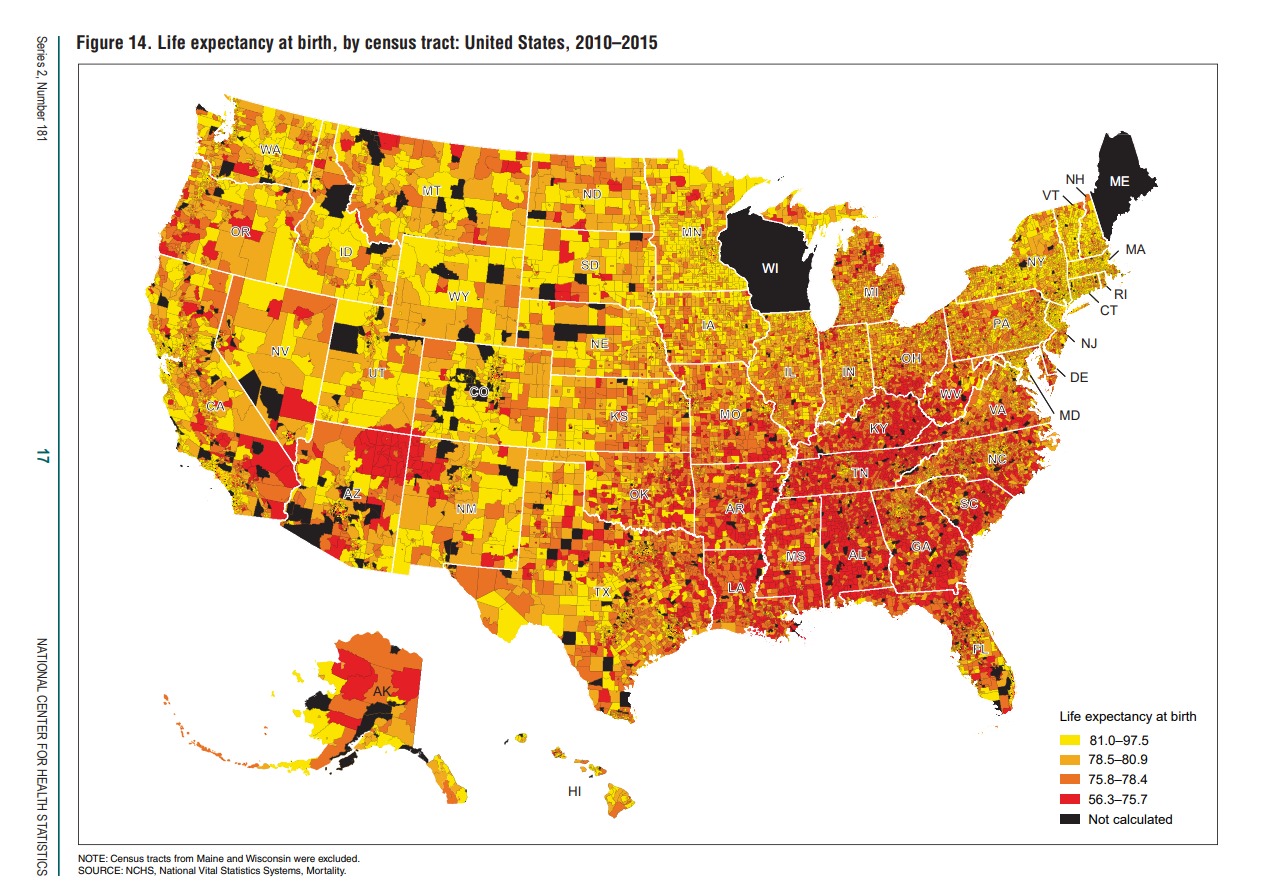

All of these systems work together to perpetuate environmental injustice, leading to significantly worse health outcomes for certain populations, especially low-income people of color. A full 60% of your health is determined by where you live, and in fact, can be predicted by your zip code.

Check out this interactive map by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, a US-based health philanthropy, that compares life expectancy per zip code to the national average. For example, a resident of Marin County (an affluent, predominantly white community in California’s Bay Area), will live ten years longer, on average, than a person living in Detroit, MI — an economically struggling, predominantly Black community.

But it doesn’t have to be this way. And that’s the main premise behind the movement for environmental justice.

A National Movement

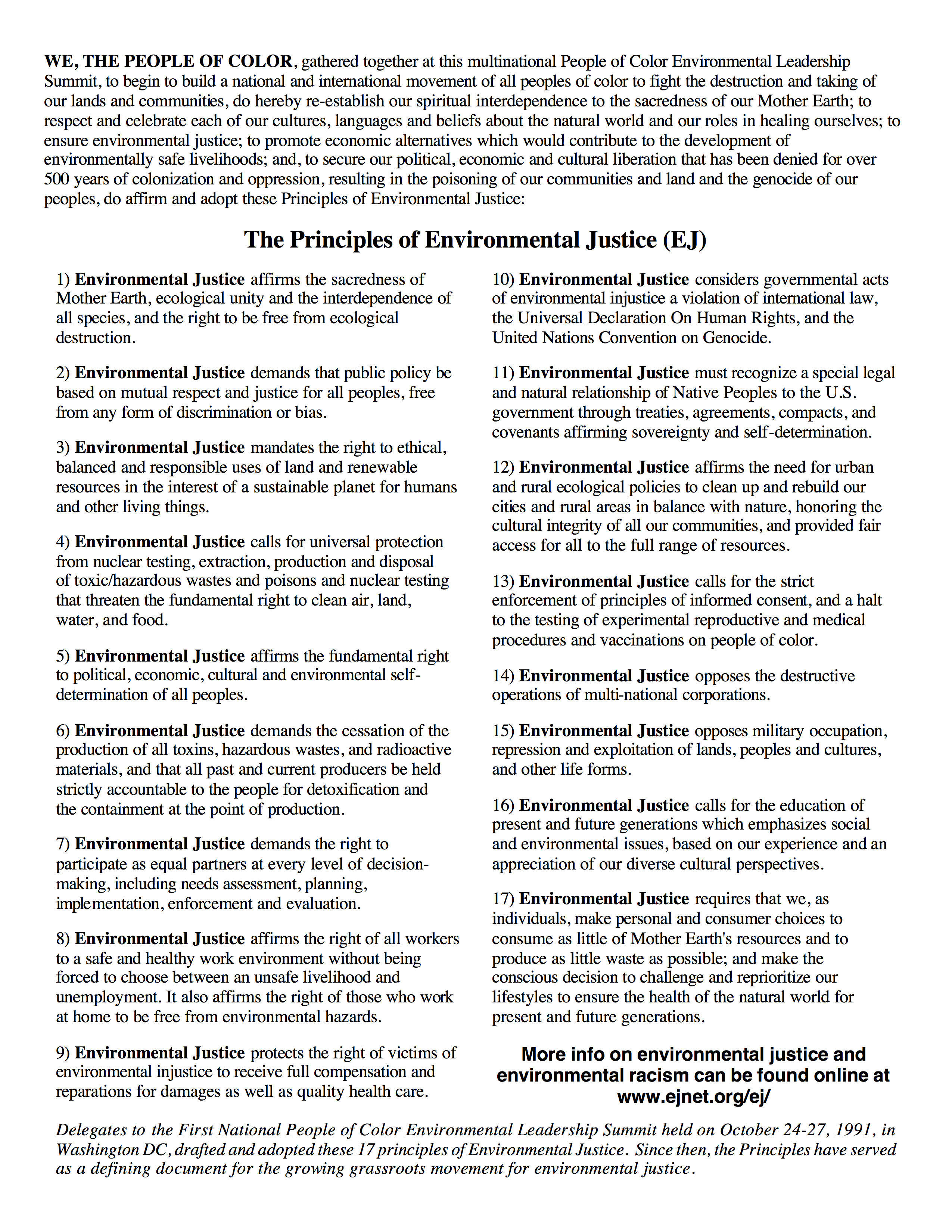

The First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, held in 1991, highlighted the power of a multi-racial, multi-ethnic, multi-regional effort to advocate for environmental justice.

In attendance were many renowned activists, including Dolores Huerta, Reverend Jesse Jackson, and Cherokee tribal chair Wilma Mankiller — as well as the heads of NRDC and the Sierra Club. By being there, they all demonstrated that the importance of environmental justice was starting to become more widely recognized. (One of the activists in attendance, Carl Anthony, was interviewed on the SpaceshipOne podcast!) Key documents like the Principles of Environmental Justice were created at the Summit to establish the movement’s framework and goals.

Since then, more EJ organizations, such as the Indigenous Environmental Network, and works like Dumping in Dixie: Race Class and Environmental Quality, began to emerge and gain traction. In the United States, policies like Executive Order 12898 during the Clinton administration devoted more federal funding towards addressing some of these inequalities.

Environmental Justice Today

The Warren County PCB Landfill was finally declared clean in 2004 — 25 years after it was built. A lot of other communities still face threats to the health and safety of their environment, and many activists continue to advocate for justice.

Environmental justice has become an essential paradigm for activism around environmental concerns, beyond toxic waste. It can involve all the different ways a community interacts with their natural and built environment, such as disparities in green spaces, transportation, and food sovereignty (to name a few).

According to a study performed by the UC Berkeley School of Public Health, there is a significant gap between diverse neighborhoods and green spaces. From 2001 to 2011, green spaces increased in white neighborhoods while decreasing in neighborhoods of color. Research has shown that green spaces boost mental and physical health, reduce mortality, and reduce exposure to pollution. Limiting these benefits to white neighborhoods deepens the burden of inequality.

One of the reasons tree cover is so important in cities is because of a phenomenon called the heat island effect. Cities are basically highly-concentrated areas of dark, heat-absorbing surfaces (i.e. concrete on roads and rooftops), which makes hot weather even hotter. In very dense cities like Chicago, the heat island effect can cause heat waves to become deadly.

Planting trees and increasing green space in these neighborhoods can provide not only more shade, but a whole host of health benefits, from physical exercise to mental wellness to greater social cohesion. There are many reputable organizations working to plant trees in underserved communities. For example, Vibrant Labs is working to “cultivate thriving urban forests that boost public health, safety, sustainability, and economic growth”.

Underfunded public transportation also widens the gap between marginalized and privileged communities. Those who rely on buses frequently spend hours traveling to places that would take half an hour by car. More hours on buses means fewer hours left each day to spend with family, making healthy meals, or pursuing interests outside of work. Inefficient public transportation can also convince people to drive cars instead, leading to an increase in air pollution, which is largely concentrated in neighborhoods near highways and interstates. Building more efficient, safe, and accessible public transportation systems can significantly improve our transportation headaches (like traffic), not to mention transportation equity. You can take action by advocating with organizations like NAPTA, who help advance public transportation policy.

Another example of ongoing environmental injustice is the lack of food sovereignty in certain areas, especially BIPOC communities. La Via Campesina, a global movement of farmers, coined the term “food sovereignty” in 1996, and describe it as: “the right of Peoples to healthy and culturally appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.”

Food sovereignty recognizes that food is so much more than a commodity; it is a sacred gift of life, that everyone must be able to access equally in order to survive and thrive. Yet, in many low-income neighborhoods, sustenance can be found almost exclusively at fast-food chains, gas stations, and liquor stores. Nationwide research has shown that these businesses are much more common in low-income areas, where the few grocery stores that do exist are less likely to stock a variety of fresh fruits and vegetables. Poor nutrition leads to a whole host of health issues, like chronic stress, obesity, tooth decay, cancer, and lowered ability to concentrate at work or school.

In 2016, this type of food insecurity was shown to disproportionately affect Black households (22.5% compared to the 12.3% national average) and Hispanic households (18.5%). For communities affected by food insecurity, solutions can include making use of food pantries and growing your own fruits and vegetables in a community garden. Community gardens have become increasingly popular during the pandemic, and early research shows that participating in one offers many other health benefits, such as mental wellness, and can also strengthen social cohesion, mutual aid networks, and community resilience.

As we continue to push for solutions to our current environmental problems, it’s important to acknowledge all the work that has come before that has built towards the transformative moment we are in now. Environmental justice must be kept at the center of our visions for a more abundant and inclusive world, or we will simply repeat the mistakes of the past. Organizing and fostering healthy communities is an integral part of the way forward.